Should the old house turn out surprisingly to be the former home of

one's own family, built and occupied nearly two centuries before and lost

to memory for a hundred years, the interest naturally must be even keener.

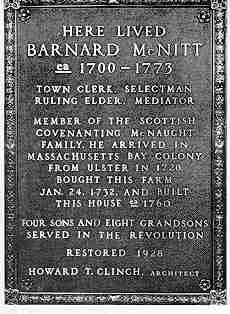

Thus was Barnard McNitt's Palmer home discovered anew in 1917.

When it was learned sons from his home had gone to the French and Indian

War and the Revolution, and that a colonizing cousin from Virginia had

come here to recruit settlers for the Acadian country in Nova Scotia, it

appeared likely the old house had a great deal of history behind it.

This work has told of the history and the associations. This chapter

is for those who because of kinship with the place would like to visit

it.

The old house looked forlorn in 1917; it had received hard treatment from a long procession of owners since 1776. Only one man after Barnard had owned it for as many as thirty years. He was Joseph Hawley Keith, who bought the place in 1863 after managing it as the town's poor-farm for

(end of page 396)

eighteen years. Then he gave up caring for the indigent elderly and began developing it, removing the big central chimney and digging a branch brook to supply water for the house. After his day the farm passed rapidly and even confusingly from one owner to another; no one seemed able to make a living there, and a big house and scenery couldn't make up for insufficient tillage land and unseasonable frosts.

The house and 100 acres of the old farm were bought from Dwight C. Hathaway at the beginning of January, 1922, by a great-great-great-great-grandson of Barnard McNitt. Restoration had to wait until the summer of 1927, and was not completed until the end of 1928. In the meantime a small brown cottage, built across the street in 1922, had been occupied by the family in summer seasons.

The wing of the old house, too far gone to be saved, was reproduced in the same dimensions to make a home for the caretaker, in advance of the main job. Restoration was directed by Howard T. Clinch, member of a firm of Boston architects skilled in the problems of early New England architecture and familiar with period detail.

The date of original building has been set approximately at 1760. A schoolhouse authorized at a town meeting in 1762 was built with similar details in exterior trim. Barnard's son William, who went to Nova Scotia in 1761 and who soon afterward designed and built a Presbyterian church at Truro, may be supposed to have had a hand in building his father's house, though other men of the family were good carpenters for generations. Asked some time after he had restored the house to suggest the date of original building, Mr. Clinch wrote:

"It would appear to me to date from about 1750 to 1775. My judgment is based on the general construction and the details of the original woodwork which remained at the time of restoration. In the districts somewhat remote from the more urban developments, the style of the architecture was apt to be somewhat earlier in period than in the larger towns where the newer trends were first introduced, which makes it difficult to confine the date within too limited a period. The fact that another house not dissimilar in general style was built in the vicinity of the Barnard McNitt house in 1750 would seem to lend probability to the belief that the latter was built at a not far different date."

Two houses in the neighborhood, in fact, appear to have been built in or about 1750. Barnard's neighbor on the east was Samuel Shaw, another Ulster Scot, and his house -- long disguised in modern times with a front porch -- has been discovered by pleased new owners, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth T. Park, to have all the evidences of 1750 construction. After Samuel Shaw, Jr., moved away the place became known as the Converse farm. Until recently it was the home of the Justin Rouvellat family. The other 1750 house is at Palmer Old Center; it was built by Captain John Thomson., father-in-law of young William McNitt. This large house is now in disrepair.

The aim with Barnard's old house was to make the restoration conform in essential detail to the original design, and to keep added features in general harmony with the type and period. The main house is forty feet long and thirty wide, and the wing on the east end is thirty-two feet long by twenty-eight feet wide. The building looks to the north.

(end of page 397)

In addition to the house and barn, a clutter of small outbuildings stood in the tall grass at the rear. These were promptly removed to make way for lawn and garden, long before restoration was begun. A young and recently-married neighbor, Norman Griffin, offered his services as caretaker and gardener in 1922. Norman was found to be an independent-spirited Yankee, very industrious, and very well qualified because of his handiness at all sorts of crafts, his knowledge of the soil, and his artfulness at transplanting trees and making things grow. He knew the lore of the forests, could name dozens of varieties of trees and wildflowers growing on the place, and could tell of the deer, the foxes, partridges, quail, and the many smaller birds that shared the premises. He was also a skilled but reticent fisherman. Though he angled trout from the brook for many a family breakfast, he wouldn't tell why he was so much luckier than others.

In 1923 another bedroom and a bathroom were added to the brown cottage, and running water was piped from the branch brook flowing along on higher ground beside the road leading to Palmer Old Center. Summer weeks were spent in the cottage for several years. On the whole, these vacations of simple living while the two boys were young, in the days when it was fun to pick blueberries, explore the upper reaches of Wigwam Brook, and rummage in the woods, may have been the best of all. Whippoorwills sound best, and fireflies glow most brightly, for a young family.

A few years before 1917 the Grand Trunk Railroad of Canada had started building a line to tidewater at Providence, and an embankment had been thrown up across the southern end of the Barnard McNitt farm. There it stood ugly, trackless, and abandoned; the scheme had been given up when the Grand Trunk bought the Central Vermont. The right-of-way across the place was bought at a tax sale, and Norman set out a screen of young white pine trees along the side of the embankment facing the rear of the big house. The young trees were transplanted from the woods; not one of them failed to thrive. Today these sturdy pines stand far higher than the top of the embankment, and with occasional white birches for contrast they serve the landscape well.

The north mowing was swampy across the center. Norman laid a blind drain of tile in a trench six feet deep and nearly 1,000 feet long, which solved that problem. Down in the hollow at the foot of the long westward slope from the big house, Wigwam Brook ran through a small swamp full of trees and rocks. Norman removed the trees and rocks, excavated widely, built a dam and spillway, and behold: a pond for swimming and for trout instead of a cathole. The spot is named Tamar Hollow on the ancient maps. The old stone walls along the roadsides had fallen down, and undergrowth had become dense in the fence rows. Norman cut the brush and built up the stone walls so they became as neat as they ever had been.

The branch brook starting at the forks up in the woods, constructed nearly a century ago to bring water to the house, was failing because a long stretch of its bed on a side hill had been washed away. Norman built a small aqueduct to restore the flow of water.

The tangle of high grass on all sides was subdued with a scythe, the ground was smoothed and seeded, and a power lawn-mower was set to whirring over a wide expanse of grass. Young trees were planted, flower gardens were

(end of page 398)

established, and Norman debated learnedly with the mistress of the place about the values of various annuals and hardy perennials. When fruit trees were proposed he was pessimistic; he argued that frosts lingered too long in spring and came too early in autumn. He was overruled; unfortunately he was proved right. The deer ate the foliage and bark off the apple trees anyway, and also the cabbages in the garden. The deer have a way of coming down from the woods into the north mowing, and standing when observed like statues, or the iron deer that once decorated Victorian lawns. It has not been uncommon for a party of six deer to visit near the house, unafraid.

The mistress of the place thought mountain laurel would look well on the hillside above the cottage to the east, so Norman found laurel bushes in the woods and transplanted them. They lived, and blossom every spring, some in pink, and some in white. He knew a spot in the woods where trailing arbutus grew, and though he brought bits of the blossoming vine he never would tell the location. Perhaps he thought it would a betrayal of the arbutus as well as the trout to let others get at them. His knowledge of woodcraft he did not keep secret; he taught the boys all they wished to know, and showed them how to make things with their hands.

Frank aspired to cut a trail through the woods and brush above the blueberry patches to the top of Cedar Mountain. It was a heavy task for a boy, and after he had struggled manfully at it and found himself tired out and still quite a way from the summit, Norman finished the job for him in a surprisingly short time. With a brush scythe he was a formidable force. He cleared a space in the woods near the cottage for a picnic ground and table, and kept on in the following winter to clear away all the undergrowth on either side of the northward road for more than a quarter of a mile. He was as competent at clearing as he was at making grow every tree and shrub and flower that he touched.

Sketches of the original floor plan of the main section of the old house show what the work of restoration entailed. The scheme was characteristic of the period of 1750 and after, with a large central chimney permitting the use of fireplaces in adjoining rooms. The front entrance hall was tiny; just large enough for doors on either side opening into a sitting room and a parlor, and for a staircase with two turns and two landings that led to a narrow hall opening into the front bedrooms on the second floor. Since the entrance hall and staircase had to be fitted into the space between the central chimney and the front door, the use of the space had to be calculated to the inch.

As in most colonial New England farmhouses, the rooms were small. The sitting room; parlor, and four bedrooms upstairs were approximately fourteen and a half feet square. At the back of the first or ground floor were a kitchen, a dining room, and a small bedroom. The original wing, entered from the kitchen as well as from the front, was a woodshed in 1917. Earlier it had contained two or three bedrooms. Reconstructed, the wing contains a roomy kitchen, a living room, two bedrooms, and a bathroom. It served as a home for the caretaker's family until a separate white cottage was built in 1932; now it is reserved for domestic helpers.

Mr. Clinch recommended a modification in design. The big central chimney had been removed many years before, so he advised a central hallway,

(end of page 399)

with a chimney at each end of the building. This arrangement permitted the staircase to rise without turns to the second floor hall, and allowed for the convenient placing of bathrooms, cupboards, and closets.

When Marie discovered the attic was high and roomy, she proposed two large bedrooms, with a hall between them, and a bathroom. Her plan was found to be practical, with the setting of dormer windows into the roof to provide ample light and ventilation. So the house was to have a third floor, for boys. The staircase from the second floor to the third was to be erected above the main stairway and was in effect to be a continuation of it in design.

The original framing was of heavy hewn timbers, mortised and braced, and held together with large round wooden pins. The rafters were of smaller timbers, hewn on the upper side only, where the roof boards were nailed. The upright timbers of the main frame were so large that they projected into the rooms at the corners, and were enclosed in box-like casings. This method of covering timbers that otherwise would project into rooms was commonly used in pre-Revolutionary houses. It is an interesting point that the upright framing timbers at the corners were not of the same dimensions all the way up, but were hewn in conformity to the tapering of the logs. The smaller ends were placed on the main sills, and the taper of the box-like enclosures in the comer rooms reveals that the hewn logs were stood on their heads when the heavy frame was erected. This placing of butt ends of timbers at the top to support the framing on which the roof was erected, no doubt was done to insure greater strength.

Well, Barnard's house was built to endure. Only the sills needed replacing with new timbers resembling the old, and most of the rafters were sound. New sills meant new joists for the main floor, as a matter of precaution. More than a century and a half of service had worn out floor boards, and they also needed replacing. Most of the original doors were in good condition, including the one at the front entrance. White china knobs had been mostly used to replace the old thumb latches; these were now to go so that thumb latches of the original period might come back. The original doors may be detected by the plugs of wood smoothly inserted to fill the holes made for the china knobs. Though panelled, the old interior doors are thinner than those used in modern construction.

These details were found to establish the date of original building in the period after 1750: 1. The rectangular sawed brownstone blocks used in the foundation at the front. 2. The design of the front entrance. 3. The handmade wrought-iron nails used to fasten the clapboards to the studding. 4. Design of the stairway, with newel posts, rails, and bannisters almost exactly like those of many other houses known to have been built at that time. 5. The decorative scrolls of wood at the outer ends of stair risers. 6. The design of window and door frames, with mouldings more elaborately detailed than was customary in farmhouses of later periods. 7. The dimensions of windows designed for sash with small panes.

The architect found not only in these details but in the whole manner of construction familiar evidence of the methods of builders in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. He resolved to retain every bit of the old detail that remained good, and to carry on the design in restoration and extensions.

(end of page 400)

Window trim that obviously had been altered after Barnard's day was replaced to conform with the woodwork that remained. Although the staircase had to be changed, the detail was kept exactly the same, and old bannisters and scrolled riser-ends were retained.

New foundation walls were necessary, and the basement was extended beneath the whole house, to join the one under the new wing. The gravelly knoll on which the house stands has a sharp slope to the rear, so the basement opens out on the grounds at the back of the house. The basement is so high, right and dry, that it affords space for a game room with pool table, a servant's room, bath with shower, a laundry room, furnace room with oil heater, pump room with a motor drawing water from a driven well into a pressure tank, fruit room, and storage for cords of logs for six fireplaces. Barnard's basement was dry, too, but it was dark and had no cement floor.

The corner sitting room at the front and west end of the main floor was extended across the west end of the house alongside the central hall. Its fireplace has a mantel from an old house in Salem, Mass. The front parlor became a dining room, and later it became a library when discovery was made that the original kitchen, provided with a big fireplace, and with walls sheathed in wide, feather-edged pine boards, offered a more informal and sociable room for dining. Across a facia board beneath the mantel-shelf of the wide fireplace in this room is carved an inscription from these lines by Robert Burns:

For this room, Norman Griffin built from a good design a hutch table with a circular top sixty-six inches in diameter, capable of seating ten persons if some of them are grandchildren. He made the top of wide pine boards that he found in an old building on the premises. The-table was finished to match the mellow color of the walls and an old pewter cupboard from New Bedford, and the top was waxed and polished so that it reflects the light of candles in their brass candlesticks.To make a happy fireside clime to weans and wife --

That's the true pathos and sublime of human life.

Years before the work of restoration was begun, New England antique shops and auction sales were visited to gather furniture and other household items of the period of the house; these were stored until the rooms were ready. The first purchase was a grandfather clock with a cherry case, bought in 1924 from a Darby and Joan in Barre. The clock remained in their shop for nearly five years. It now stands in the main hall, crowding the low ceiling, and ticking away placidly. A banjo clock with the name of Aaron Willard on its face hangs on the wall at the far end of the living room, above a Connecticut gateleg table. Inside the clock was found a card with this inscription: "This clock formerly owned by Gen. John Stark of New Hampshire - dicitur." That is, it is said that Gen. Stark, victor at Bennington, once owned it. Anyhow, it keeps accurate time.

It was fun to prowl all over New England. In New Bedford were found brass thumb-latches and a curly maple candle-stand besides the pewter cupboard; on the Cape, Hepplewhiite arm chairs and a sewing table; in Springfield a tambour desk for the mistress and a Governor Bradford desk with serpentine front for the study; in Marblehead ladder-back Chippendale

(end of page 401)

chairs; in Ipswich hooked rugs; in Boston an old Windsor arm chair and other things. Wherever she could find them Marie picked up opalescent mirror knobs for curtain tie-backs at the windows.

And so on. Those who have furnished a house in like manner will understand. Days like those before the great depression are no more, and the burden of other enterprises taken up since makes it seem fortunate that Barnard's old house was restored and plenished before the crash of 1929 ushered in an era of austerity that was prolonged through the second World War.

Reclamation of the old homestead has been assisted by cheerful friends whose part deserves remembrance. Very soon after frequent mowing of grass began between the house and pond, robins came more numerously in the early springtime. Perhaps there were a dozen at the outset. Each year they have increased in number, always in pairs, with older robins returning and bringing others. Now the robins are almost beyond counting. Observing them, one may learn what robins like. They are especially active on the days when the lawn-mower is at work, following the fresh swath and pecking away in the close-clipped grass for food.

The robin colony is permanent because of the mower that makes foraging easy, and the house brook that flows through the lawn to the pond, providing fresh water for bathing and drinking. The robins believe the place is theirs. They build nests in the pine trees and the lilac hedge, introduce their young to good hunting in the lawn, and the running spring water, and make their plans for the coming season before flying away at the outset of drouthy weather. Should the summer prove comfortable with frequent rains, they stay on.

One mother robin for several years had her own hemlock tree for her nest, on the far side of the pond, and she laid claim to a patch of damp ground beside the water, where the hunting was especially good. Should another parent attempt to gather food from her garden, Mistress Robin drove off the intruder with angry cries and pecks.

Robert Duckworth, a caretaker in recent years, has a robin story of his own. He relates that he heard a great commotion in a small evergreen tree, and observed a mother bird hauling a blacksnake away from her nest with bill and claws. Is this believable? Bob got out his shotgun and dispatched the snake; for his story he has two credible witnesses. Never underestimate the power of a mother! There are no other snake stories: not enough snakes to count.

The robins are not the only resident birds. Barn swallows build their nests of mud and twigs under eaves and on projecting woodwork on the back porch. They are not afraid. In the spring of 1949 a pair of swallows scaled up the porch door by building their nest on the doorstop of the screen. A census of the migrant bird population visiting the premises shows other varieties, more shy than the robins and swallows and not so chatty around the house, but still fond enough of the woods and streams to come often.

Among those who come and go are cardinals, bluebirds, Baltimore orioles, bobolinks, red-headed woodpeckers, bluejays, humming birds, killdeer, meadow larks, red-winged blackbirds, woodcock, ruffled grouse, pheasants, sparrows, scarlet tanagers, catbirds, downy woodpeckers, blue herons and

(end of page 402)

brown thrushes. Sometimes wild ducks pause to rest on the water of the pond. Occasionally there may be a hawk or an owl.

An oriole's nest hung lately by its four cords from one of the lower branches of the great elm behind the house. Among the most beautiful of the birds are the wild canaries: small, swift, and brilliant in coloring, with black wings and tails setting off the rich deep yellow of their bodies. They flash among the elms, and fly away too soon.

The constant apprehension in late autumn is that hunters will disregard posted signs and take shots at the partridges, quail, and deer. The hunters swarm the woods from the first morning of the open season, and it is possible the deer are fewer now than they were four or five years ago.

Apart from the time of flowering of iris, narcissi, oriental poppies, lilacs and peonies, the most beautiful season is in early October. After the sharp frosts have nipped the maple and oak leaves and given them all the colors from golden yellow to deep scarlet: then is the time to see the place at its mellowest. It offers a serene welcome.

(end of page 403)

Send e-mail