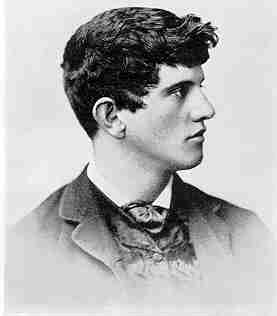

Francis Augustus MacNutt at 16

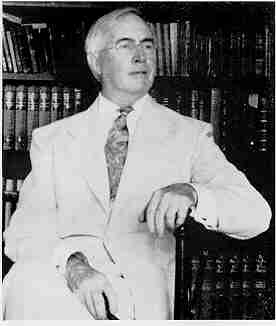

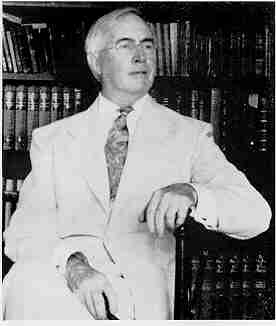

and at 50

J. Scott MacNutt, painter - See p. 188

His portrait of his son Francis

Francis Augustus MacNutt at 16 |

and at 50 |

J. Scott MacNutt, painter - See p. 188 |

His portrait of his son Francis |

So Francis Augustus MacNutt could have been portrayed with understanding in a novel by Henry James. Only, however, when James felt equal to a work of epic dimensions. In Francis' expatriate life in Mexico, London, Constantinople, Madrid, Rome, Vienna, and the Austrian Tyrol he felt more of the Jamesian aspirations, met more dowagers and diplomats, princes and court ladies, Cardinals and Popes, than even James himself might have thought credible enough to include in a work of fiction.

The grandson of Barnard McNitt in the fifth generation was what the scientists would call a "sport" -- a complete departure from the norm. He could have been a study for another novelist -- a fellow Hoosier named Booth Tarkington -- who would have been entertained by his aspirations for European society and his avidity for brilliant ceremonies and spectacles.

This descendant of the rugged Massachusetts farmer was born in Richmond, Indiana, on February 15, 1863. His father was Joseph Gideon McNutt, son of John Murray Upham McNutt, both lawyers in Ohio. The former was a Captain in the Quartermaster Corps of the Union Army when his second son was born at the home of maternal grandparents: Andrew Finley and Martha McGlathery Scott. Their daughter Laetitia lived only a week after the baby Francis was born; they gladly undertook the care of the child and of his brother Albert, not quite three years older.

John Murray Upham McNutt, the paternal grandfather, was born in Nova Scotia on July 26, 1802. He was a grandson of William, son of Barnard McNitt of Palmer, who had married Elisabeth Thomson in the new Ulster-Scottish community in Massachusetts and welcomed three children before joining Alexander McNutt of Virginia in 1761 in the colonization of Nova Scotia. John came down to New Jersey as

(end of page 143)

a youth to finish his education, moved to Ohio in 1821, and was admitted to the bar in Preble County in 1823. He married Jane Hawkins of a Virginia family in 1828. In his brief but active life of thirty-five years he served two terms in the House, and two in the Senate, of the Ohio Legislature. He had a taste for literature, and the library of fine books he left, including works in French and Spanish, was a source of pride to his grandson Francis.

Andrew Finley Scott, the maternal grandfather, was typical of the Ulster Scots who peopled the Valley of Virginia. His grandfather, Andrew Scott, came from Ulster to the vicinity of Lexington and was a neighbor of the McNutts of Virginia. Andrew's son Jesse was a Jeffersonian Democrat who disliked slavery and freed the few slaves he owned when the abolition movement became a stirring issue. Jesse's son Andrew Finley, born in 1811, moved to Indiana and became a successful banker and man of affairs, as well as a staunch leader in the United Presbyterian Church.

The wife of this greatly respected Richmond banker was Martha McGlathery, also of the race of Ulster Scots. Her grandson Francis wrote of her in later life that she loved her two grandsons passionately; that "passion" was the only word to describe accurately her various moods in her relation to others. She had a temper she did not try to control, and her husband Andrew kept his calm by a habit of silence when under fire at home, and by devoting himself to blameless interests outside.

"His manners were uniformly urbane and simple," Francis wrote of his grandfather. "Under his apparent gentleness, there lay a strong will and tenacity of purpose that amazed any who inadvertently ran foul of his convictions and decisions. Noting the firm line of his mouth in repose and the keen look in his blue eyes, deep-set under beetling brows, a close observer would have divined that Andrew Scott was not all sweetness. Never have I known anyone so indifferent to, so quietly defiant of, public opinion."

Grandmother Martha had been beautiful as a young woman, and still was slender and straight in carriage. As a means of escape from family discords, "traceable, directly or indirectly, to her unhappy disposition," she devoted herself to flowers and animals, which responded glowingly to her care.

This rapid sketch of the background of Francis Augustus MacNutt is necessary to an understanding of the manner in which his life took shape, and became what he made of it. He must have been handsome as a boy; his photographs in later life are those of an unusually good-looking man.

(end of page 144)

In youth he had a kind of insolent charm, and the bearing of a patrician. It is clear that he felt himself in every fiber a patrician, and entitled to a place in the world's aristocracy.

When Francis Augustus grew old enough to inquire into his origins and to analyze them with reference to his idea of what he stood for, he became apologetic for his covenanting ancestors and wholly disinclined to pride in what they had done. He turned rather to the Hawkins family: his grandfather John Murray Upham McNutt had married Jane Hawkins, of a family that had left Devonshire for America when Catholics were placed under disabilities by severe laws against their religion.

It may be that the Hawkinses adhered to the spirit of the Cavalier tradition, though they may not have been of it precisely. Their scion who found himself enmeshed in a quite different tradition, regretted that they had frittered away "the precious heritage of the Catholic faith." They may have begun their frittering long before they left England, through neglect and intermarriage with Protestants. But for Francis they had Virginia glamor: "Of the men, those who were not soldiers turned to the law, and all of them were high-spirited and given to good, possibly the best, living." Of Jane's father, Joseph, it was said in his day: "When Hawkins snuffs, the county sneezes."

Toward the end Francis Augustus MacNutt wrote an autobiography -- Six Decades of My Life -- a readable work written in a warm and often brilliant style that came from experience in writing and editing several books that had preceded it. Reference is made to it here because it has been a helpful guide in the preparation of these chapters.

A central fact in the life of Francis Augustus was his instinctive turning to the Catholic faith in childhood, despite the objections of his Presbyterian grandparents, and his passionate adherence to it through all his years. He was a Catholic of Catholics; probably he became far more deeply absorbed in matters of creed, dogma, canon law, traditions and ancient customs than most others whose families had been Catholic for many generations. His creed meant far more to him than loyalty to family and country.

By his own account he was not pious, nor was he in the least devout in the spiritual sense. From childhood he hungered for beauty; in the ritual of the Mass, the ceremonials and processions, the lights, the music, the vestments, the sacred objects of the altar, images and statues, stained glass windows, and stately architecture -- all hallowed by the usage of centuries -- he found a kind of beauty that he craved. When the consecrated work of the priesthood was offered him, he resisted. He had

(end of page 145)

no vocation for it, he confessed honestly. Eventually glamorous work useful to the Church was found for him, that gave him great satisfaction for a while.

We are reminded of another youth from a Presbyterian home who was charmed by the Catholic manner of worship: James Boswell of Auchinleck. But Boswell lingered only at the threshhold and never entered; his inner compulsions were different.

Whence the spontaneous call to which the child responded? Answering this question in later life, Francis Augustus asked himself another: could it have been "the workings of an atavistic force transmitted, untainted, through perverted Protestant channels from some devout Catholic ancestor?" Perhaps the Calvinist doctrine of predestination had something to do with it, he decided. But perhaps the circumstances governing his early home life had an influence he didn't measure.

His grandmother's acerbity kept the home atmosphere taut and uncomfortable. Perhaps the boy felt ill-adjusted: always groping for warmth and beauty. When he was about six he wandered one day through the open door of a plain little Catholic church near his grandfather's home: the church of St. Mary's, where a congregation of poor Irish people worshipped -- families whose men worked on railroads and in factories. Father McMullen must have been surprised when the grave youngster rang the doorbell of his house and announced he had come to call. Francis saw the kindly priest several times, and the priest explained to him the uses of objects employed in the services.

One day on leaving the church he encountered two nuns, Sister Mary Carmel and Sister Mary Ildefons, who took him through the parish school and to their house. Both were kind, but Sister Mary Ildefons was beautiful in the boy's eyes, with "bright blue eyes, nice teeth, and the sweetest dimples imaginable." He visited them many times; they answered his questions without asking any; perhaps they gave him cookies. Now we may find here a simple answer that Francis never published, even though he may have thought of it: the gentle nuns may have supplied the warmth craved by a motherless boy, and thus have influenced the whole course of his life.

As time went on, Francis obtained from a Catholic bookshop a crucifix, two candlesticks and candles, and a rosary, and with a discarded desk in the attic for an altar, he went secretly at night to tell his beads and commune alone. When Father McMullen learned he was a grandson of Andrew Scott, he explained to the boy that it was improper to come without his grandfather's knowledge, and directed him to come no more. The visits with the nuns were continued; the sisters would not

(end of page 146)

turn the boy away. When Francis was about eight or nine, Father McMullen conscientiously told the grandfather.

Andrew Scott was kind, but firm in telling the boy he must not visit Catholic churches; perhaps he explained the Protestant view of the veneration of images and of ceremonials in Latin, and the emotional problems of a celibate clergy denied the normal outlet of love for wives and children. The boy listened but did not obey; he visited Catholic churches whenever he could when he was away from home.

Francis' father came for an occasional visit from Eaton, Ohio, where he had his law office. On one of these visits, the grandmother sought to put the boy to shame by telling at table of his secret explorations in Catholicism. Joseph McNutt, himself an Episcopalian, amazed all by saying after a moment's scrutiny of his son that it was a pity all were not Catholics; that the Reformation had been a calamity. He concluded by saying: "Catholicism is the aristocracy of religions."

"The aristocracy of religions!" The words rang chimes inside the boy's mind. The phrase pleased him: "I hoarded it up for future meditation and use," he afterward wrote. But his grandmother was irritated, and he had never seen his grandfather "so visibly vexed."

Devoted grandparents are often at the mercy of children in their care, especially if they have money, as the Scotts did. A child can take accurate measure of the limits to which he can go, and press an advantage, if he chances to have a mind set upon a maximum of gratification and a minimum of responsible effort. Andrew Scott could give his spirited and handsome grandson good counsel, but he never could control or even influence him in the use of money. Consequently Francis indulged princely tastes as he grew older, and his plain-living grandfather paid all the bills.

Francis was started in school at eight, and after a little he was placed in a Quaker academy. He had several music teachers, who could not do much with "a lazy, refractory boy who refused to practice." But Professor Ruhe won his admiration and taught him the meaning of music, and appreciation of the masters. Finally he said: "Frank, you are ambitious; if only you were poor and diligent you might become a great artist." This perhaps was the most poignantly revealing thing ever said to him about his relation to work and life. The poor and diligent often reach heights not accessible to the darlings of fortune, though the latter may believe until their final stock-taking that having lived richly they have followed the better course.

When Francis was thirteen his grandfather took him to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Less than a year later, in March 1877,

(end of page 147)

his father died in the Richmond home after a long illness that had taken him to Colorado for relief, and to the South in winter. The hidden qualities in Mrs. Scott came into evidence as she nursed her sick son-in-law with affection and devotion. Writing later of this bereavement Francis said: "I had no strong affection for my father. I hardly knew him." Brother Albert came home from school: "I hardly saw him and this death did not draw us nearer together."

In 1879 Francis entered Phillips Academy at Exeter. A photograph made at the time shows a straight-nosed, strong-jawed youth of sixteen who could look the world defiantly in the eye. The academy at Exeter, then as now, maintained scholastic standards not excelled elsewhere in this country, and a boy who could get through comfortably was certain to have no trouble in any university if he kept on working. Francis made friends and enjoyed himself. Here he developed a new interest: on half-holidays he often hired a horse and trap (the liveryman may have called it a buggy) and searched the neighboring country for antique furniture and china with which to deck his room. Thus began a collection.

English literature and United States history interested him; he subsequently concluded that the history texts contained "misleading nonsense." He came to understand what Latin meant, and this knowledge became useful later. At the end of his second year he was unable to pass his examinations, and that terminated his experience with Exeter. During the summer vacation at Richmond he went dutifully with the family to the Presbyterian church, enduring "dreary hours in the unlovely conventicle, listening to dull, endless sermons," unrelieved of course by any kind of pageantry.

Harvard was next. He couldn't enter the college because he hadn't passed his final examinations at Exeter, but he could enroll in the Harvard Law School. He had no slight wish to be a lawyer, but a year or two at Harvard, he thought, would provide interesting experiences while he considered what he might later do. His furniture and bric-a-brac had been sent over from Exeter, and Grandfather Scott had a look at the collection when he came with Francis to Cambridge before the autumn term opened. Andrew Scott said plainly that the rooms didn't look like those of a student. Francis was glad when his grandfather left, after arranging to pay for books and tuition and to supply $1,800 in expense money.

Well, that was quite a year for Francis. From his own account we learn that he developed into an embryo dandy, and accumulated a wardrobe. When his pockets were empty he could get easy credit, and when

(end of page 148)

bills pressed, he could find a money-lender. Or when he wanted another suit, he could take to a second-hand shop some clothing that had been new a few weeks before. Boston is a haven for collectors, and diligent exploration of antique shops resulted in vast accumulations to crowd his rooms. His collection of colonial teapots alone expanded to thirty-seven examples.

The most memorable event of the year was a visit from Oscar Wilde to Boston on a lecture tour. Oscar was famous as a wit, and as much so as an exquisite, and it was bruited about Harvard that the character Mr. Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan's light opera "Patience" was a caricature of him, with perhaps some reference to James McNeill Whistler. Bunthorne the esthete always carried a lily, presumably because Oscar Wilde was said to be fond of carrying a lily. A group of Harvard wags conceived the idea of getting two rows of scats immediately in front of the platform for the Wilde lecture, attending decorously in the garb of disciples, carrying lilies and sunflowers. Francis accepted a bid to join the group of sixty in the rite of mock worship.

On the day before the lecture, Wilde was entertained at tea in Cambridge, and Francis was one of a party of about eight student guests. The young men were charmed. Oscar wore his hair a bit long; otherwise he seemed as other men, with no lily, but with a delightful flow of brilliant conversation. After he had gone, those who had undertaken to bring ridicule upon him at his lecture were embarrassed. It seemed not the sporting thing to do, but they had promised, and they went, hoping the celebrity from England would not recognize them.

News of the prank got about in advance; perhaps having heard a tumor, Wilde did not appear in silk knee breeches and braided coat as expected, but in conventional evening dress. Francis was seated in the middle of the front row, not more than six feet from the lecturer's desk, feeling vastly uncomfortable. When Wilde came to the front of the platform in the midst of welcoming applause, he smiled down amiably at the group in burlesque outfits, and gazing directly into Francis' eyes he said: "Et tu, Brute?" When the audience became quiet, Wilde began: "I have but one prayer to offer this night -- Lord, deliver me from my disciples."

Next morning Francis received an invitation to lunch with Wilde at the Hotel Vendome. He had been singled out for special favor; no other student was among the men present at the luncheon. Wilde seriously urged Francis to visit England and Oxford, asked him to send word when he would be coming, and promised to help him get to see Oxford at best advantage. The visitor was of course pleased at having turned

(end of page 149)

the tables on the sixty students, and spoke appreciatively of Harvard and the hospitality shown him.

Toward the end of the academic year Francis found he was approaching an economic collapse; a tailor had sued him, and bills continued pouring in. Theater parties, supper parties, sleighing parties, and livery hire all had cost money, and a piano had come to live among the antiques. "It seemed to me," he wrote in later life, "an endless horde of vulgar people was pestering me for money which I did not have."

A friend he called Jim, dropped from Exeter, begged him to join in a year's stay in Europe with a Belgian tutor who was expected to coach him in preparation for the Harvard entrance examinations. Would Grandfather Scott pay off the bills and finance a quiet, studious year in Belgium? It seemed hardly likely. The bills amounted to more than $3,000 in excess of the $1,800 allowance.

Let us make brief the sad story of Grandfather Scott: he agreed to pay off the bills, and after first positively refusing, consented to back his young prince for a year in Europe. We cannot help wondering whether he believed it would be a quiet and studious year. When he consented he lost all prospect of further control; he was but wax in strong young fingers, and Francis knew it. Andrew Scott let him go because he did not know what else to do with him.

Back in New York before sailing, Francis emerged one day from Delmonico's restaurant to walk into Oscar Wilde. On learning of the trip, Wilde proposed giving him letters of introduction, and asked his New York address. A packet arriving that evening contained letters introducing him to James McNeill Whistler, Alma-Tadema, and Rennell Rodd in London, and to Philip Burne-Jones in Oxford. A note urged Francis to use the letters, as Wilde meant to write to all four, announcing his coming.

The young man had done some reading on architecture and English literature between whiles at Harvard, and felt quite at home in England. He attended plays, and opera at Covent Garden, and visited the art galleries while awaiting a propitious time to use his letters. Alma-Tadema asked an account of Oscar's escapades in America, and the young visitor was at pains to explain he had seen little of him; that all he knew was what he had read in the newspapers. Rennell Rodd took him to see Whistler, who insisted upon doing a sketch of his head. It was for the "Augustan forehead," Rodd explained to him. The week at Oxford was delightful.

Next came a brief stay in Bruges, and then Brussels, where Francis studied French for two months under Jim's tutor. The tutor's mother

(end of page 150)

died, leaving him a competence, and he quit his work immediately. Jim notified his father, who replied that he would come to Europe and bring his son back home with him. Before they separated, the two young men journeyed in a leisurely way to Cologne, Lucerne, and Geneva; then on to Turin, Milan, and Venice. Thence to Verona, and over the Alps to Munich, Dresden, and Berlin.

On arriving at Berlin, Francis found waiting a letter from a young Richmond friend: Ida (not Daisy) Miller, who was studying German in Hanover. He joined her and took up the study of the language himself, having discovered the need in his travels. Ida Miller was a Catholic, and while in her company Francis decided the time had come for him to be received into the Church. The only place for him to take the step, he determined, was in Rome, the fountainhead of his faith. He wrote his grandfather of his decision, and set out on his pilgrimage by way of Genoa, Florence and Pisa.

The entrance to Rome in January 1883 gave him a feeling of homecoming; the city enchanted him. On February 15 he reached his twentieth birthday, and soon thereafter he set about his great undertaking. After a three weeks' retreat in the Passionist Monastery of SS. Giovanni e Paolo on the Celian hill, Francis was received into the Church without hesitations on either side.

In Rome he encountered again an Irishman of striking personality he had met in Bruges: Monsignor de Stackpool. He seemed a kind of special personage, with undefined clerical functions, and a great deal of interest in society and in important visitors to the Holy City. He concluded Francis was a young man of fortune and was instrumental in getting him introduced to persons of rank. He even talked of the youth to the great Leo XIII, and introduced him to the Pope at a semi-public audience. Whatever the Monsignor may have been saying, he persuaded an important circle that here was an "interesting case."

Francis sought to correct the impression he was a millionaire, and when a dismayed letter from Grandfather Scott almost threatened to cut him off with a shilling, he told Monsignor de Stackpool of his embarrassment. The Monsignor then spread the word among friends that the youth had bravely risked his inheritance for the sake of his faith.

Then followed a season of exploring St. Peter's, the catacombs, and the more beautiful and interesting churches and monasteries of Rome. Also: "I attended endless religious ceremonies, some of them stupendous, pompous festivals, in which gorgeous processions moved amidst clouds of incense overweighting the air already laden with the scent of burning wax and the bitter-sweet odors of crushed laurel and ilex leaves,

(end of page 151)

while the too-dulcet strains of the decadent music then in favor were rendered by the celebrated choirs of the Sistine and the Lateran. Every manifestation of religious faith interested me."

While the grandparents sat in the United Presbyterian church in Richmond and grieved over the apostasy of the young wanderer, Francis made his triumphant way in the Catholic society of Rome. Sponsored by Monsignor de Stackpool and Lady Herbert of England, he made his bows in the salons of Princess Altieri, Princess Piombino, Duchess Salviati, and Marchesa Serlupi. He was immensely pleased with the spacious grandeur of the Roman palaces where he was so kindly received. He met several Cardinals of the Roman aristocracy, and others who were not Italians; titled persons, and rich women of fashion from his native land.

Francis was confirmed on the Feast of the Assumption in the chapel of the English College in the presence of a few distinguished persons summoned by the Monsignor; a supper in the Stackpool apartment followed. Soon afterward he left for Venice, Vienna, Budapest and Munich; thence to Bayreuth for a season of Wagnerian music. He next saw Paris, "not without profit," but he always deprecated Paris in writing about the city, with the implication that its wickedness chilled him.

On reaching London he made use of two letters of introduction he had carried from Rome; they had been received from Bishop Chatard of Indianapolis, member of "a good old colonial family of Maryland." One letter was to Father Antrobus of the Oratory in Brompton Road. The other was to Cardinal Manning.

There was something in the bearing and personality of the young man that won for him unusual consideration from his elders. Cardinal Manning's secretary received the young man from Indiana, and invited him to come to dinner that afternoon at one-thirty. The Cardinal had several other guests; after speaking with them he took Francis by the arm and led him to the dining room, seating him next at the left. The young stranger was greatly impressed by the ascetic countenance of the Cardinal, as well as by the shabbiness of his dress. Cardinals in Rome had looked gorgeous; here sat the most illustrious of all with the red silk of his sleeves worn threadbare.

After soup and the reading of verses from Scripture, the Cardinal turned to Francis and asked about his travels. When the party broke up after prayers in a chapel next the dining room, His Eminence requested Francis to join him upstairs after a few minutes. In his library the Cardinal pressed Francis for the story of his entrance into the Church, and all the circumstances that had led to it. When the guest

(end of page 152)

was about to depart, Cardinal Manning gave him a book entitled The Love of Jesus for Penitents, saying:

"This little book, the smallest I have ever written, may commend itself to you by its brevity." On the title page was inscribed: "F. MacNutt, from H. E. Card-Archbishop Oct. 4,1884."

As Francis was leaving with his treasure the Cardinal told him kindly he must never visit London without coming to call; that if he ever needed a service he must not fail to let it be known. Then, "Remember that I am your friend."

Francis now had been away from home for a long time: the quiet year of study in Belgium to which his indulgent grandfather had consented in the summer of 1882 had been extended to more than two years of brilliant experiences. What should he do with his life? What was he fit for? "I had not the means to lead the life of a man of leisure," he afterward wrote, "besides the insignificance of such a life was repugnant to me." He wanted something else, something more. What was it? He did not know. He could find no answers to his own questions.

So he went back to Richmond, Indiana, sailing from Liverpool late in 1884. His grandfather, he learned, had proudly caused to be printed in a home newspaper parts of his letters telling of his travels. The domestic atmosphere to which the prodigal returned seemed intolerable to him. His grandmother spoke eloquently and often of the ingratitude of children and grandchildren. Francis wanted to go away, and no one urged him to stay. He thought he would like the South; his grandfather's half-brother Jesse Scott lived in New Orleans; that was a city to see.

After the glories of Europe, life in his own country seemed dull to the young traveler. On the journey by river from Cincinnati he found the boat shabby, food poor, service wretched. "Sitting in the upper deck, I could hardly believe that the vast stretch of muddy water, flowing turgidly between the low, featureless banks, was the great Mississippi, the river I had been assured was the largest, the most beautiful in the world. It was neither the one nor the other." Could he have forgotten, when he wrote these words, the turgid, muddy waters of the Tiber, the Po, and the Danube?

New Orleans did not long detain the wanderer. Observing pictures of Mexican scenery in a steamship office, he bought a cabin ticket on a boat soon to leave for Vera Cruz. Jesse Scott applauded his judgment.

In Mexico his spirits rose again as he viewed the grandeurs of scenery that made the Alps seem insignificant to him; Mexico City was wonderful in his eyes. He received from his faithful grandfather a letter of introduction to the American Minister, which opened the way to new

(end of page 153)

acquaintances. Then came a singular friendship that was to influence his life for years.

One night in the Hotel Iturbide an Indian servant called him to the side of a man in another room who seemed to be dying. At the bedside he looked down at an "emaciated face of singular beauty and refinement, framed in thin, curly, silky black hair." The man's eyes opened, the most wonderful eyes Francis ever had seen, he thought. The face had an expression of "limpid, saint-like innocence." In a whisper the sufferer said he was English, a priest, the chaplain of Cardinal Manning; his name was Kenelm Vaughan. Francis had left Cardinal Manning only a few weeks before; Father Kenelm was a brother of one of his friends in Rome.

The young man hurried out to look for help; an hour passed before he could return with a priest. He found a friend of the sick man had come with a physician, and so departed. Next morning he returned to the room to find it empty; Father Vaughan and his luggage had vanished. But an hour or so later, in the street outside, Francis met Father Vaughan, who was carrying a small terra cotta figure of the prophet Jeremiah. Then began the unusual friendship.

The ascetic priest, who appeared to be about forty, explained he had been traveling up and down Latin America in an undertaking to found a new secular congregation in what he called the Work of Expiation. He planned a central house in London, and had been organizing a society of founders, each member of which contributed 50. No smaller gifts were accepted. His work had the approval of the Pope, he said, and he carried a letter from Cardinal Manning.

The two men were immediately drawn to one another, and after Father Vaughan had heard Francis' story he insisted that the young man become a priest and join him in a penitential life in expiation of the sins of mankind. Francis demurred that he had no vocation, but he was soon in the tutelage of the Abbé Fischer, curate of San Cosmé, a fashionable suburb of Mexico City. The Abbé, born in Germany, had been associated in Mexico with the Archduke Maximilian at the time Napoleon in had proposed that he become Emperor of Mexico. It was he who had prevailed upon Maximilian not to flee from Mexico when the intervention of the United States made the imperial scheme hopeless. Remaining to face death at the hands of republican-minded Mexicans, Maximilian had entrusted to the Abbé a bundle of papers and correspondence bearing upon the ill-fated project.

Now came a course of instruction in a number of subjects that lasted for months; the Abbé was an excellent tutor. But he did not care for

(end of page 154)

what he heard of the Work of Expiation. He told Francis the plan was chimerical and expressed the opinion Father Vaughan was a visionary; he also came to the conclusion the young man was not adapted to the priesthood. After he had become acquainted with Francis' inclinations he advised him to choose the career of historian, and encouraged him in the work of translating into English the letters of the Spanish explorer Cortes to Charles V.

The Abbé Fischer became so deeply attached to his pupil that he offered to sell his library and collection of rare coins, together worth a considerable amount, to provide means to finance the early years of historical work. He went even further. The collection of Maximilian papers he had stored in London was desired by the Austrian court because certain of the letters would prove embarrassing if published; the Abbé had been offered in exchange for them a considerable sum of money, a pension, and the privilege of spending the rest of his life in an Imperial castle on the Dalmatian coast. Now he proposed to accept the offer, surrender the papers, invest all the cash proceeds in property that would provide a steady income for Francis, and assist in historical studies in Europe. The Abbé then could retire to the Dalmatian castle. Furthermore, he would make the young man his sole heir.

After learning of the disapproval of Grandfather Scott in Indiana for Father Kenelm's project that Francis become a priest in the Work of Expiation, the Abbé Fischer began a correspondence with Andrew Scott. Francis learned afterward of this, and of his grandfather's agreement with the Abbé that the idea of the priesthood must be discouraged.

The Abbé clearly had become devoted to his pupil, and frankly said the youth's coming had changed the whole nature of his lonely life. But Francis was uneasy. A contest had developed between the Abbé and Father Kenelm for ascendancy in his companionship, and the Abbé's plan for developing his talents as historian cut squarely across other plans Father Kenelm had been unfolding. The Work of Expiation as he perhaps outlined it to Francis was not to be altogether expiatory for the sins of mankind. It was to include a number of interesting trips, sojourns in archepiscopal houses, and varieties of exciting adventures.

In this rivalry over Francis the younger priest won. Francis announced that he would go away for a while to visit Mexican friends, and then would return home to Richmond, but already he had engaged to meet Father Kenelm soon again in New Orleans. All the generous offers of help toward historical scholarship were refused. The Abbé Fischer was desolated at the final parting, when he presented Francis with a small framed portrait of St. Francis Xavier by Murillo. Thus ended sadly for

(end of page 155)

the older man a friendship that was only one of a series of remarkable ones in Francis' life.

In his own account of his rejection of the Abbé Fischer, Francis attributed his coldness to what may have been only a chance remark on the part of his mentor. Various suspicious Mexicans had concluded Francis was a long-lost son of the Archduke Maximilian, supposed to have died in infancy. Francis was credited with having a Hapsburg chin, and this fancied resemblance, together with the Abbé's interest in him, encouraged fear that the Abbé was bringing along an aspirant who meant to be monarch of Mexico. When the Abbé said of the story, "Too bad it isn't true," he planted the seed for a later rank growth of speculation regarding his possible plans for another coup d'etat in Mexico, to put Francis on a throne.

This seems absurd. The Abbé was old and without power. Francis preferred the company of Father Kenelm, and the chance remark gave him an excuse for following his inclination. But he relished, no doubt, the wide belief he was a scion of the House of Hapsburg though he took pains to contradict it. His later attachment to Austria and the cause of its royal house may have flowered from his reflections on his Hapsburg chin, and musings on an impossible throne in Mexico.

(end of page 156)

Send e-mail